There were a couple of by-elections in the UK this week, both in traditionally-safe-ish Labour seats.

Normally in the sixth year of Conservative government, this would be a boring event that nobody cared about: a medium-strength opposition wins government seats at by-elections (even if, as with Labour under Neil Kinnock pre-1992 and under Ed Miliband pre-2015, it will go on to narrowly lose the general), but even a weak opposition holds its own seats.

However, the times right now aren’t normal, and so Labour was seen as under threat – from the shambolically dumb and awful neo-fascists of UKIP in depressed former pottery town Stoke on Trent Central, and from the Tories in part-ex-industrial-towns, part-nuclear-power-plant, part-grumpy-farmers Copeland. The threats were real. As the fascists imploded, Labour beat them by a not-exactly-resounding-but-better-than-feared majority of 2,620. Meanwhile, the Tories won Copeland with a majority of 2,147.

This fits the post-Brexit course of UK politics: Labour’s performance in 2010 and 2015 was artificially propped up because the kind of traditional Tories who don’t-want-a-person-of-colour-for-a-neighbour voted UKIP. Now that the Tory party is led by a petty authoritarian who hates everything from after 1953, rather than a toff who loves money and doesn’t really care very much about anything else, these people have gone back to the Tories.

Labour’s hilariously awful leadership and infighting over the last 18 months hasn’t helped, and certainly hasn’t provided an alternative narrative, but at worst Jeremy Corbyn and his backstabbier rivals are drilling new holes in the bottom of a ship that was already leaking and on course for the rocks anyway.

What does any of this have to do with popularity?

After the election, Momentum true believers – both within the Labour party organisation and outside – displayed an Iraqi Information Minister-ish commitment to presenting the results as a Great Victory. I was particularly struck by the quote in this tweet:

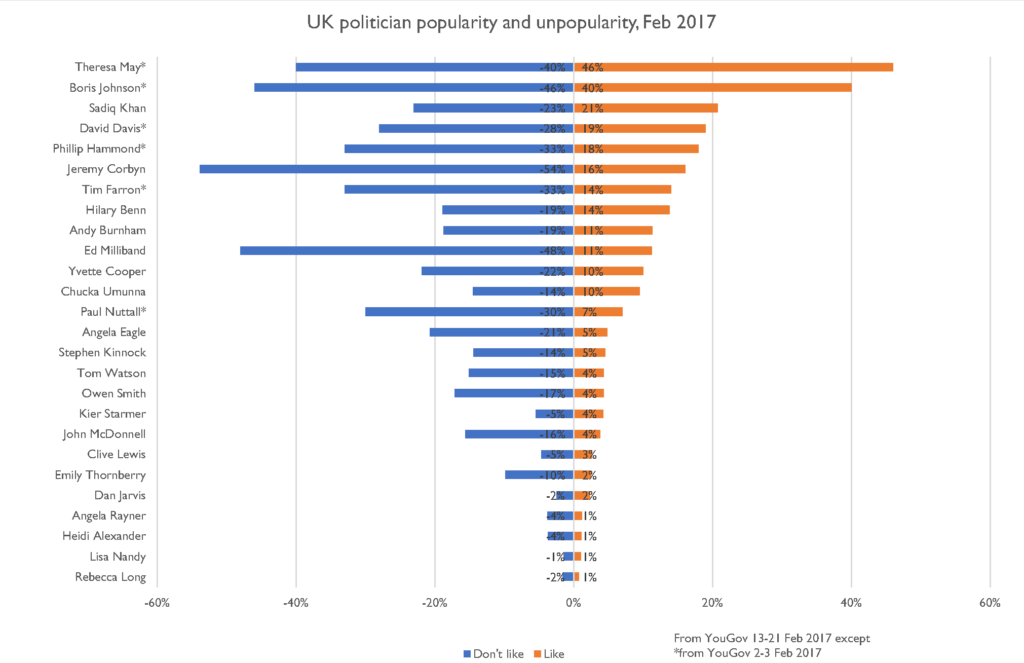

Ian Lavery MP says Corbyn "one of the most popular politicians in the county". Current approval rating -40%. #bbcdp

— Jack Blackburn (@BlackburnJA) February 24, 2017

On the face of it, Lavery’s claim is ridiculous. But there are some completely reasonable definitions of ‘popularity’ under which he has a point.

Like most of the people reading this piece, I would score net favourability of zero in an opinion poll, because only a niche selection of transport and politics wonks have the slighest idea who I am. In one sense, that makes me 40 points more popular than Jeremy Corbyn. But in another sense it’s silly to say that I’m vastly more popular than Jeremy Corbyn, because if I organised a weird cult rally in my name then the turnout would be nobody; probably not even my boyfriend, and certainly not 50,000 Momentum pod people.

The difference here is gross and net popularity. Both are important in political leaders, depending on the kind of organisation they lead and the kind of electoral system within which they operate, but we tend to dwell on the net numbers. So, I’ve put together a chart aggregating poll results in order to show gross popularity and unpopularity of various UK political leaders, which reflects the fact that most people haven’t heard of most of them:

This is based on two slightly different YouGov polls – one from 2-3 Feb 2017 of famous politicians and one from 13-21 Feb 2017 of Labour politicians (PDF). YouGov calculated the numbers for non-Labour politicians; I calculated the numbers for Labour politicians.

So the claim that Jeremy Corbyn is one of Britain’s most popular politicians is defensible. On gross popularity, he’s the sixth-most popular current Westminster politician, of the ones for whom I could find recent data. At the same time, he’s the most unpopular current Westminster politician by a fairly wide margin.

The problem here comes when we think about when the two different sorts of popularity are relevant.

If you want to dress up as an evil clown and sell albums to dumb flyover state poor people, then being extremely unpopular on net but with high gross popularity is a route to immense success. If you want to push horrific far-right ideas into mainstream UK discourse and then fuck off to America to do speaking tours to dumb flyover state rich people, then likewise.

On the other hand, if you want to become President of France, then the runoff electoral system means that you need decent net popularity. The two candidates with the highest gross popularity will get into the run-off, but then the candidate who the voters of France hate the least will be the winner. This setup kept Jean-Marie Le Pen out of the Élysée in 2002, and hopefully will keep his daughter out this year.

The UK Labour Party, traditionally, competed in the President of France space: a centre-left party that people voted for under the UK’s antiquated first-past-the-post electoral system because they thought it was less awful than whatever the Tory Party was up to at the time. That requires leadership with decent net popularity, and high gross popularity isn’t very important.

However, Corbyn’s popularity is the opposite: someone who has a strong enough following of fervent weirdos that their success condition is “shifting the acceptable window of mainstream opinion”. This isn’t a bad thing in its own right; there’s a reasonable argument that we need a Farage-of-the-left to counter the global rise of far-right ideology. The probem is that at the same time, it isn’t a particularly great idea for either side to chain such a movement to a moderate centre-left party seeking to defend its position in hundreds of FPTP seats.

Header image by The People Speak / CC-BY 2.0.